By absorbing about a third of man-made carbon dioxide (CO2), the ocean decelerates global warming. However, when dissolved in seawater, CO2 reacts to produce carbonic acid, causing seawater pH to decrease. It also diminishes the concentration of carbonate ions, thereby putting organisms forming their shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate at risk. Apart from plankton, algae, mussels and snails, stony corals are among those particularly endangered: Their skeletons consist of aragonite, the most soluble form of calcium carbonate.

“Model calculations indicate that if CO2-emissions continue at current rates, more than 70 percent of cold-water coral reefs known today will be exposed to conditions corrosive for calcium carbonate by the end of this century. It seemed obvious, therefore, that these corals will be among the first to suffer from the effects of ocean acidification”, explains Ulf Riebesell, Professor of Biological Oceanography at GEOMAR. “But our results do not support this”, adds the Kiel marine biologist Dr. Armin Form. “For the first time ever, we showed that the globally widespread species Lophelia pertusa keeps growing even in corrosive waters if given the time to adjust to the new conditions.” Armin Form and Ulf Riebesell now presented their results in the renowned journal Global Change Biology.

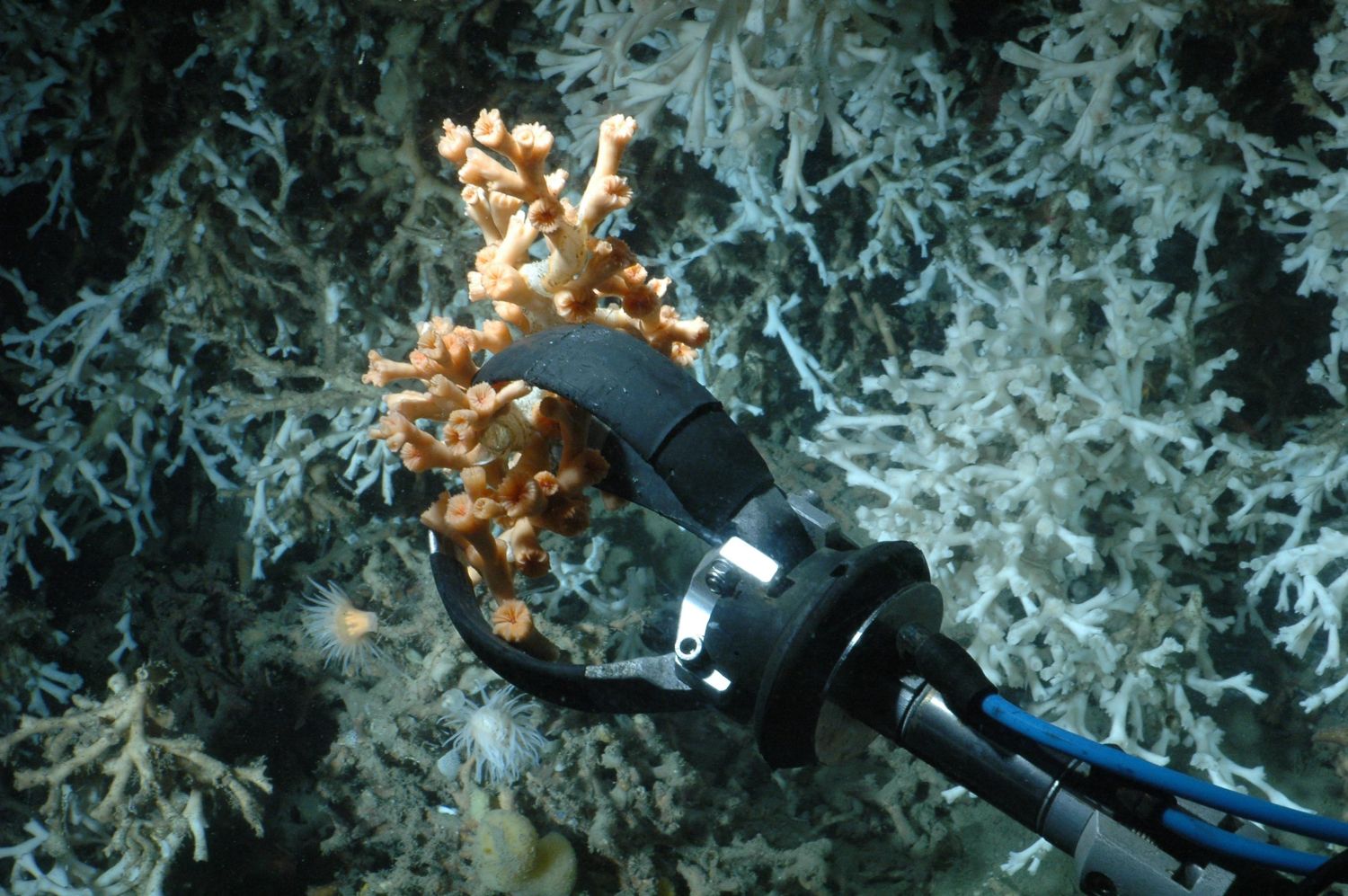

In a first experiment, the scientists kept selected coral branches in bioreactors for a week at a range of CO2-levels as projected to occur during the next decades and centuries. The temperature was held constant and the corals were fed properly. A second experiment under similar conditions took six months. “The short-term experiment suggests that even a pH decrease of only 0.1 units results in a decline of growth by about one third compared to control conditions”, Dr. Form summarises. “But the long-term experiment did not support this trend – to our own surprise and that of the marine science community. The corals seem to get used to the new conditions. Maybe the acidified water even provoked a counter-reaction, because on average the corals under high CO2-conditions even grew faster compared to those in the controls.”

Dr. Form and his colleagues regard these experiments as a first step in understanding the effects of ocean acidification on cold-water corals. “But ocean acidification is just one aspect of climate change. Not only increases the acidity of seawater, its temperature also rises”, stresses Dr. Form. “At rising temperatures, cold-water corals need larger amounts of food to maintain their metabolism. It will therefore depend on the availability of food whether and to what extent corals can adjust to climate change.”

Under the umbrella of the German research project BIOACID (Biological Impacts of Ocean ACIDification) new experiments are now carried out in Kiel to investigate the interactions of carbon dioxide level, temperature and food availability. The German research vessel POSEIDON brought samples from Norwegian coral reefs to Kiel in September. Some of the corals are kept under their accustomed conditions. Others are exposed to different combinations of elevated carbon dioxide and temperature, saturating or limiting food quantities. Physical and chemical parameters of the seawater and growth and metabolic rates of the corals will be measured in long-term incubations.

“This experiment will address the question if and at what price cold-water corals can adapt to the upcoming environmental changes”, Dr. Form announces. First results are expected by the end of 2012.

Reference:

Form, Armin & Riebesell, Ulf, 2012: Acclimation to ocean acidification during long-term CO2 exposure in the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa. Global Change Biology, 18(3), doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02583.x

Contact:

Dr. Armin Form, Tel +49(0)431-600 1987

aform@geomar.de

Maike Nicolai (Communication & Media), Tel. +49(0)431 600-2807, mnicolai@geomar.de

…