Strong earthquakes such as the Tohoku earthquake off Japan in March 2011 are among the largest natural disasters in recent years. The consequences of the quake which triggered a more than 30 meter high tsunami will remain visible for a long time. But even less powerful quakes in the sea or underwater - so-called submarine landslides - can lead to flooding of coastal areas or destruction of infrastructure such as offshore platforms, submarine cables, or pipelines.

From 23 - 25 September 2013, more than 130 scientists and industry representatives from around the world were discussing the current results of this research, as part of the 6th International Symposium on Submarine Mass Movements and Their Consequences. This, the world's most important meeting of this kind, was organized by the Cluster of Excellence "The Future Ocean" and the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and was being held in Germany for the first time ever.

Submarine landslides are among the most important phenomena in the ocean. Like landslides in the mountains which alter the appearance of valleys, submarine landslides change the appearance of the continental margins, the transition from the shallow coastal zone to the deep ocean. Submarine landslides should not be underestimated as a natural hazard and can - depending on their size - trigger tsunamis several meters high - with devastating consequences for densely populated coastal areas and coastal industrial plants.

The causes of landslides in the sea are diverse and subject to controversial debates in the scientific community. Submarine landslides are mostly triggered along the so-called "weak layers", sedimentary layers with little stability compared to the surrounding seabed. Just as an avalanche slab may detach from a mountain, entire slope sections may slide down the escarpment. Participants of the symposium discussed when and why the slopes slide and also the role of vibrations caused by earthquakes. "While earthquakes are the most common triggers for landslides, weak layers probably determine the type of the landslide. Still unclear, however, is the exact composition of such weak layers and whether such weakness is the result of an earthquake," summarizes Professor Sebastian Krastel-Gudegast from the Institute of Geosciences at Kiel University and organizer of the conference.

An important component in the study of landslides is the deciphering of past earthquakes. But the records of data measurement go back only about 100 years, too short a time to be able to indicate the frequency with which large earthquakes can recur in high-risk areas. "Predicting whether and when an earthquake will cause a slope to slide is still somewhat of a lucky guess," says Professor Michael Strasser from the Geological Institute at ETH Zurich. "With the still limited data, we are essentially in the age of the Farmer’s Almanac of past centuries." In recent years, Strasser led the first campaign to drill landslides specifically triggered by earthquakes. With new measurement methods and technically advanced drilling systems, the researcher and his colleagues have explored especially the continental shelves off Japan where continental plates collide and earthquakes are repeatedly triggered. "Soon we hope to gain important insights into the recurrence rates of earthquake-triggered landslides," says Strasser. Like many other researchers, the geologist takes soil samples from drilling ships to investigate the age and stratification of collapsed slopesin detail. For example, they want to find out how and why a slope started to slide and whether it might have been the cause of a historical disaster or tsunami.

But not only the risks originating from unstable slopes were discussed in Kiel: Slopes are of great scientific interest in other respects as well because of the large amounts of raw materials, such as oil, gas and precious metal ores, stored within them. In addition, researchers can decipher climatic trends of the past from the sediment layers, as well as nutrient cycles in the ocean.

Background information

The 6th Symposium on Submarine Landslides and their Consequences is supported by the International Geoscience Programme (IGCP) 585 "Earth's continental margins. Asessing the Geohazard from Submarine Landslides (E-Marshall). E-Marshal is a joint initiative of UNESCO and the International Union of Geological Sciences. The symposium is held every two years and brings researchers together from all areas of the geosciences.

E-MARSCHAL - www.igcp585.org

Concurrent with the conference, a paper will be published that summarizes the current state of research: Sebastian Krastel, et al.: "Submarine Mass Movements and Their Consequences - 6th International Symposium", Springer Publishing House, ISBN 978-3-319-00971-1

Link: http://rd.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-00972-8/page/1

Conference programme:

http://www.geomar.de/en/research/fb4/fb4-gdy/research-topics/6th-international-symposium/

Links

www.geomar.de, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel

www.futureocean.org, Cluster of Excellence 'The Future Ocean'

Contact

Professor Sebastian Krastel, Institute of Geosciences, Kiel University, Phone: 0431-880-3914

skrastel@geophysik.uni-kiel.de

Professor Michael Strasser, Institut of Geology, ETH Zürich, Phone: 0041-44 632 61 50

strasser@erdw.ethz.ch

Friederike Balzereit, Public Outreach, Cluster of Excellence 'The Future Ocean', Phone: 0431-880-3032 / 0160-97262502

fbalzereit@uv.uni-kiel.de

Andreas Villwock, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Kommunikation & Medien, Phone: 0431 600-2802

avillwock@geomar.de

…

Press material

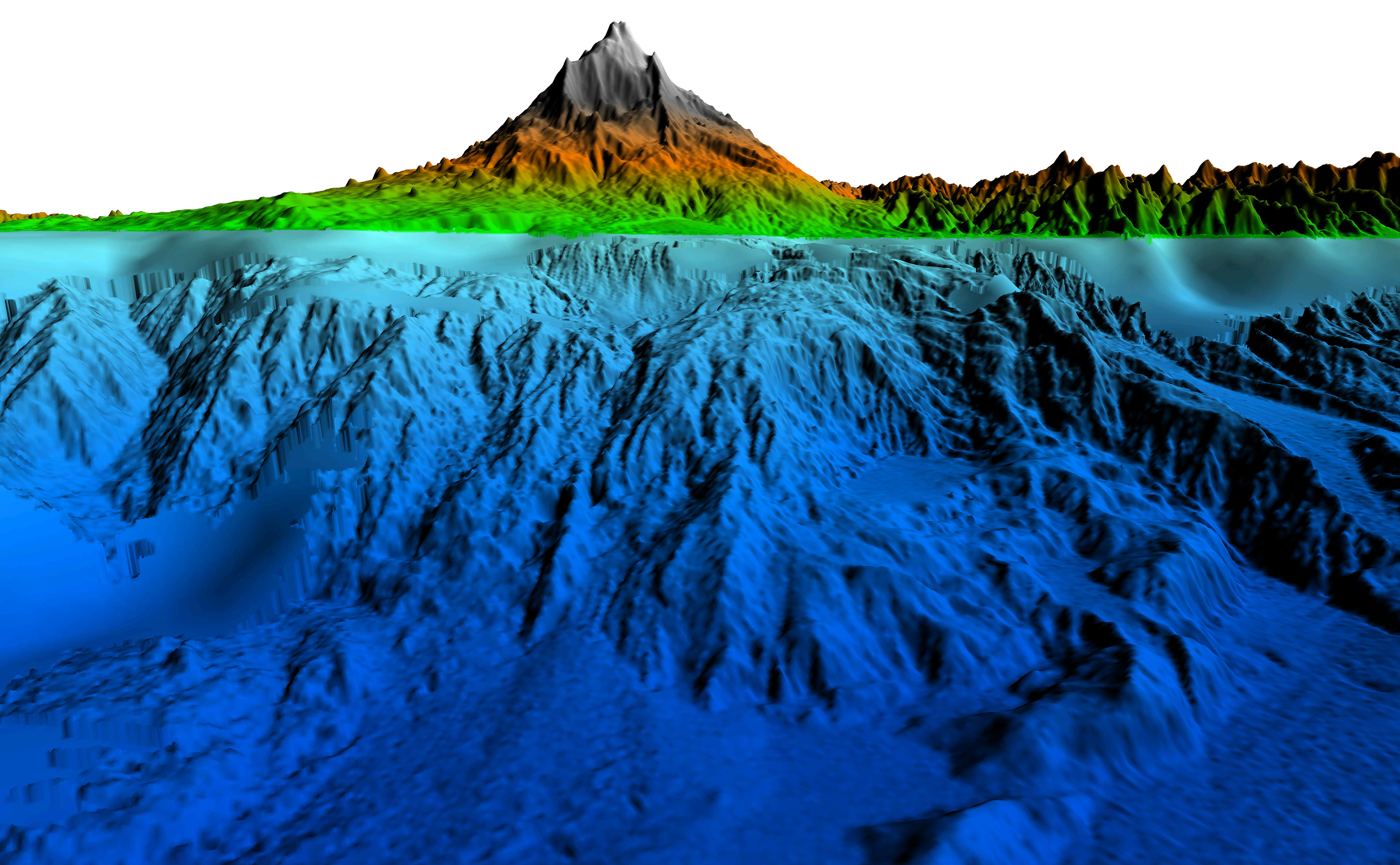

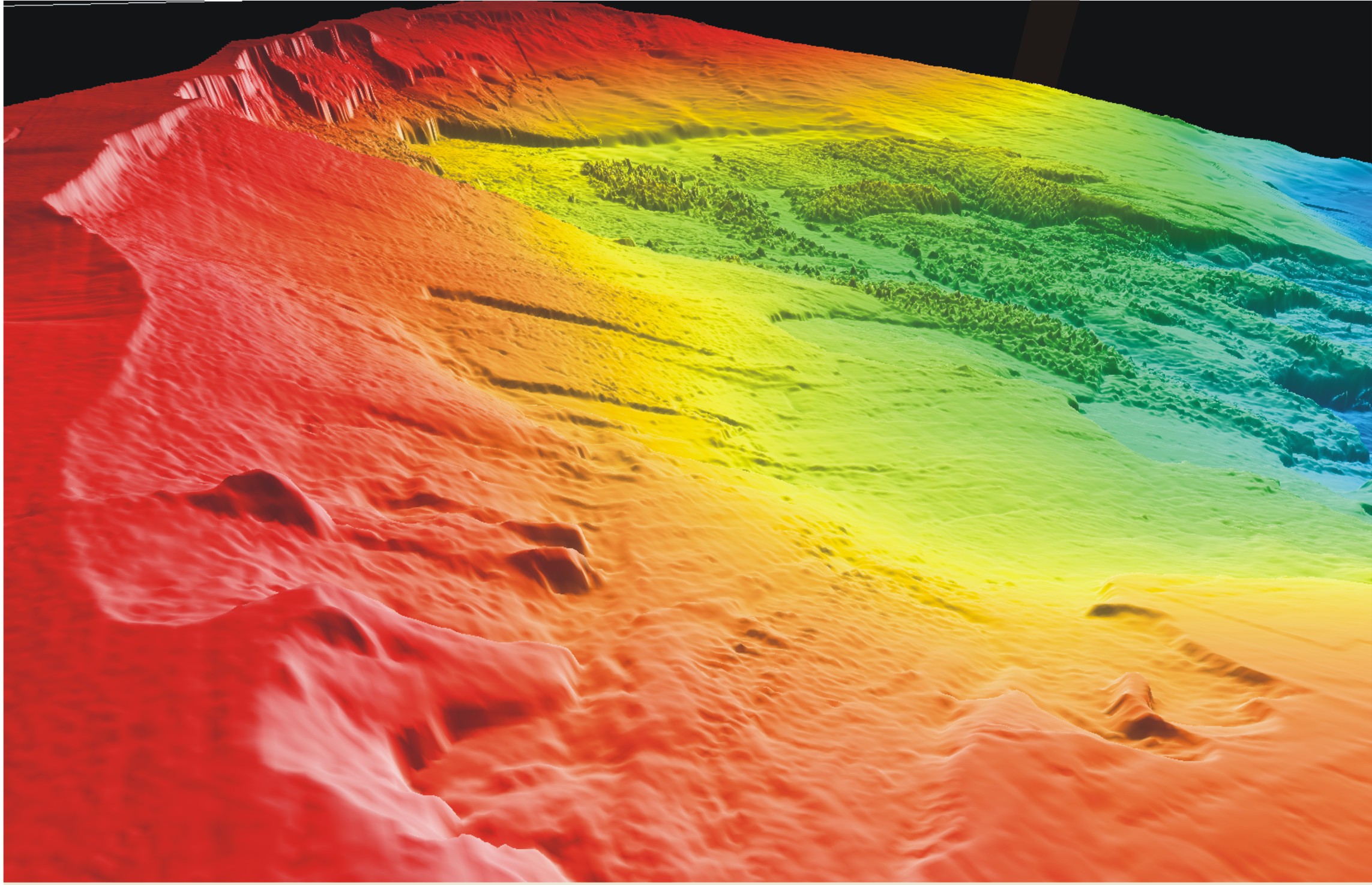

Submarine eastern flank of the volcano Mount Etna in Sicily. In the Mediterranean earthquakes are among the most common triggers of landslides.

Graphics/Image: Felix Gross, GEOMAR

Expedition aboard the research vessel METEOR in the Strait of Messina off Sicily to study submarine natural hazards in the Mediterranean. The volcanic eruption of Mount Etna can bee seen in the background.

Photo: Julio Beier, Future Ocean

Deployment of 3D seismic instruments from the research vessel METEOR off Sicily. The volcanic eruption of Mount Etna can be seen in the background.

Photo: Sebastian Krastel, Future Ocean