Whether researchers look in the sediments of the deep sea or in the ice of the polar regions, they now find microplastic particles even in the most remote places on the Earth's surface. However, relatively little is known about the effects of this man-made pollution. Some species of whales and seabirds have been documented to die if they swallow too many larger pieces of plastic. But realistic studies of the effects of microplastics, particles smaller than five millimeters, on other marine organisms are scarce.

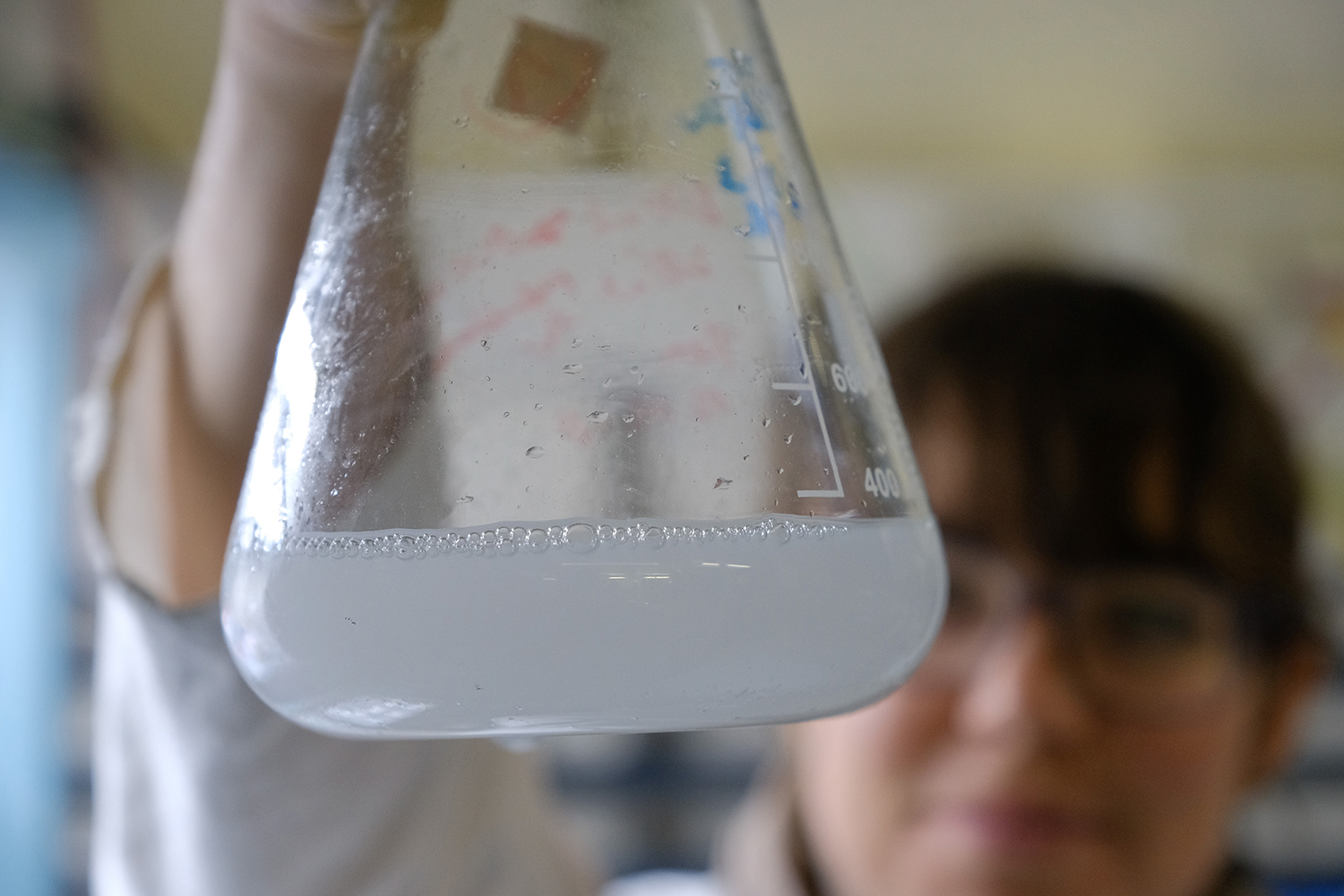

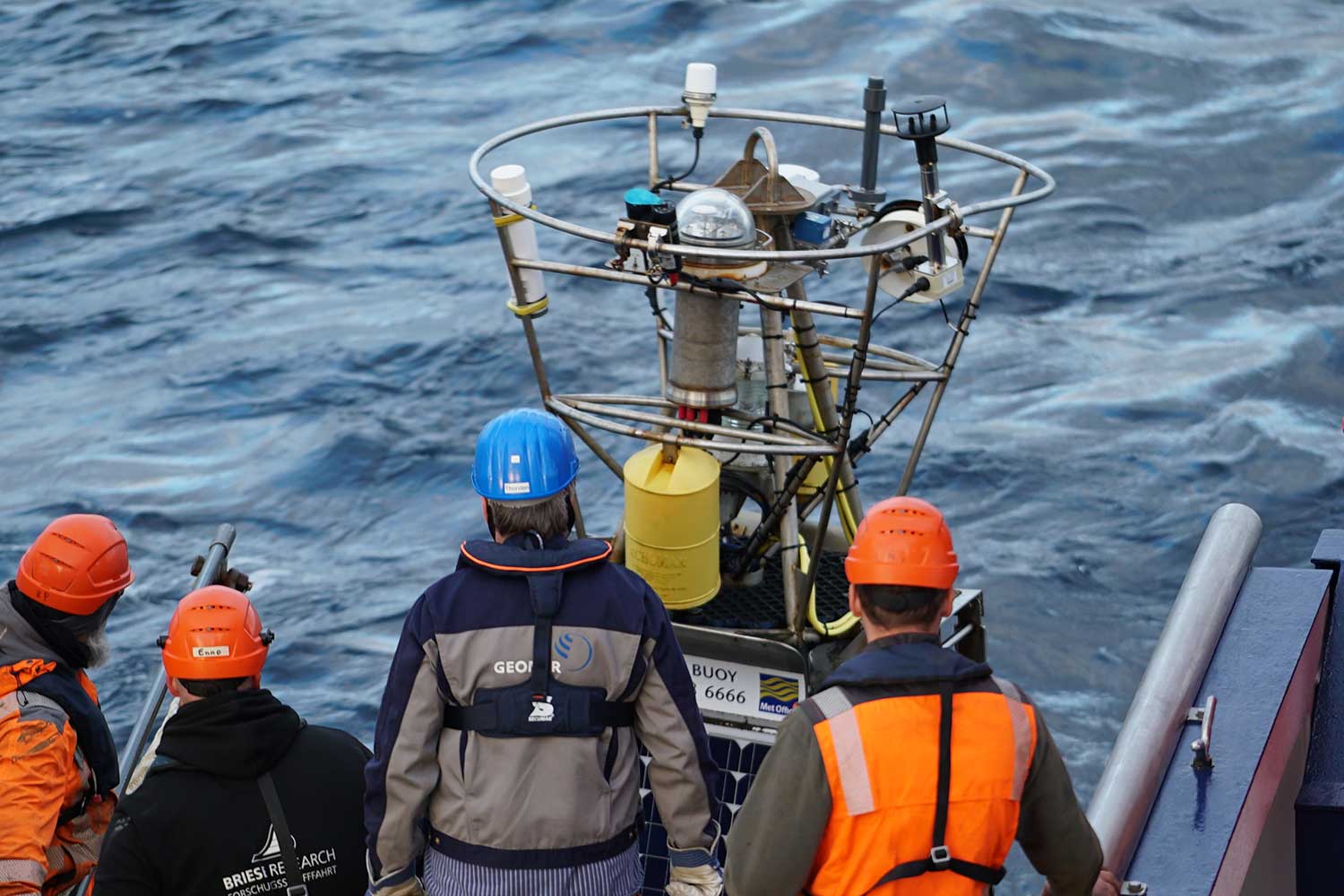

Two scientists from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have now published the results of the longest laboratory experiment to date on the effects of artificial microparticles on blue mussels in the international journal Science of the Total Environment. "Contrary to widespread fears, our study shows that mussels are hardly affected by microplastics in the water, even over a longer period of time," says Thea Hamm, lead author of the study.

Blue mussels are particularly well suited as a model organism for such studies as they are common in many coastal ecosystems. To feed, they filter seawater and inevitably ingest microplastics present in seawater.

Thea Hamm exposed young mussels to various concentrations of microplastics over a 42-week period. "What's special about this study is not only the long period of time, but also that the pollution in the experimental tanks corresponded to levels that we actually measure in the environment," says the biologist. Dr. Mark Lenz, her co-author, adds, "Many previous studies only ran for significantly shorter periods of time and used unrealistically high plastic concentrations. This, of course, can falsify the picture."

To make the experiment even more naturalistic, Thea Hamm also tested the mussels' reaction to different microplastic types and sizes. "We used uniformly round particles, such as those used in cosmetics, but also irregularly shaped ones, such as those produced when larger pieces of plastic break down," reports Thea Hamm, for whom the experiment is the basis of her doctoral thesis.

During the experimental period, she measured various values that allowed conclusions on the condition of the mussels. These included, for example, the growth rate of the young mussels, the production of the adhesive threads with which they cling to the substrate, and the rate at which they filtered food algae from the water.

Negative effects of the microplastics on the performance of the mussels occurred only late in the experiment and were rather weak. Thus, this longest laboratory study on the subject to date suggests that microplastics - at least at the concentrations in which they currently occur in the ocean - pose little threat to mussel populations. "This is initially reassuring news. But it does not mean the all-clear as far as microplastic pollution in general is concerned. Other species may react differently. We simply need more long-term experiments under realistic conditions," concludes Thea Hamm.

Reference:

Hamm, T. A. & M. Lenz (2021): Negative impacts of realistic doses of spherical and irregular microplastics emerged late during a 42 weeks-long exposure experiment with blue mussels. Science of the Total Evironment,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146088

…