Used in fuel cells, it provides energy for various applications, and only produces water as a waste product. At the moment, hydrogen is primarily obtained from the electrolysis of water - and this process initially requires energy input, which has so far mostly come from fossil fuels.

A climate-neutral hydrogen economy, i.e. the use of so-called green hydrogen, requires that hydrogen production is based exclusively on renewable energy. Researchers are trying to exploit such a sustainable energy source, for example by means of photosynthesis. Ever since, photosynthesis has provided mankind with energy from sunlight, either in the form of food or as fossil fuels. In both cases, solar energy is initially stored in carbon compounds, such as sugar. If these carbon compounds are exploited, CO2 is liberated. Photosynthetic CO2 fixation is essentially reversed in order to recover the solar energy from the carbon compounds.

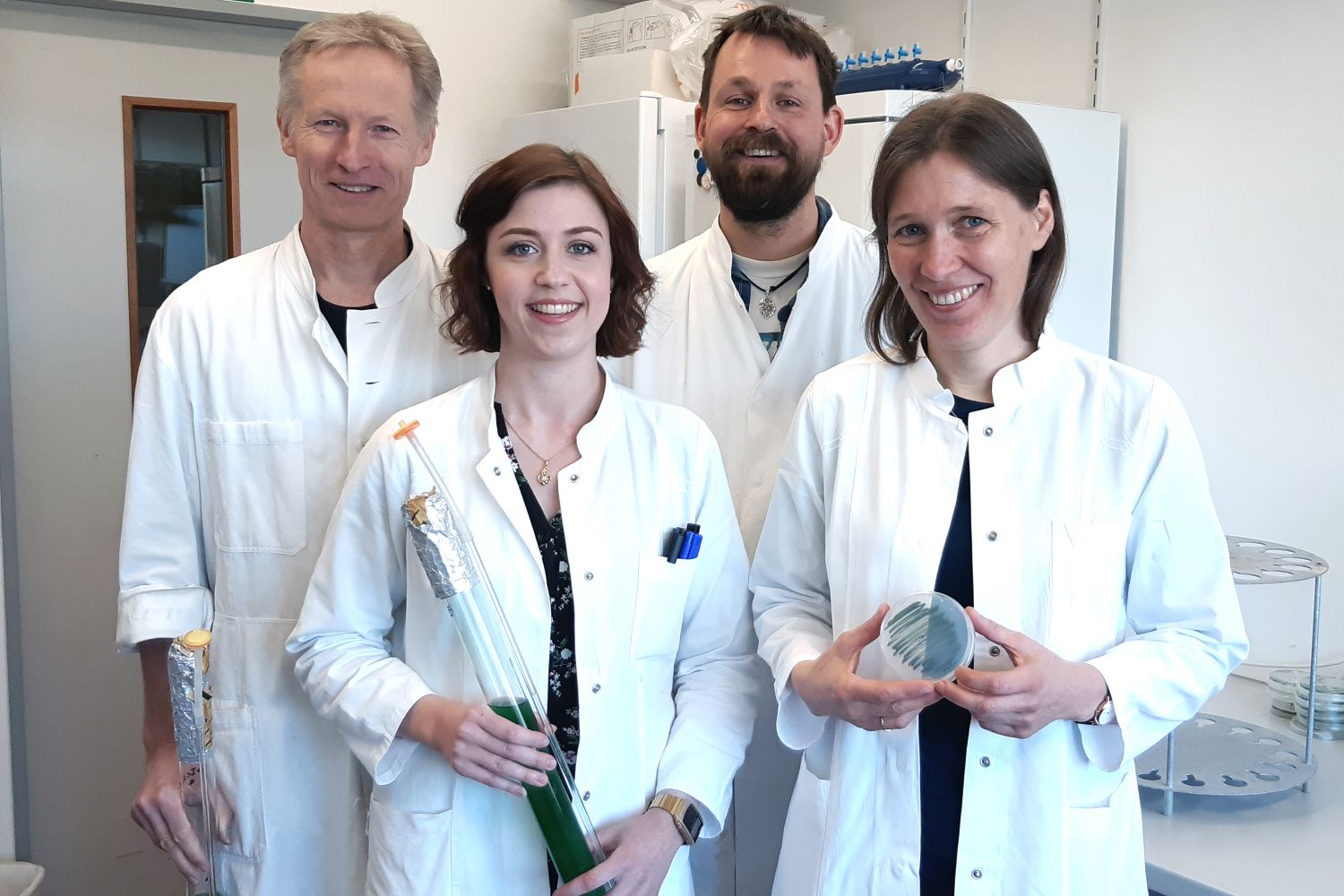

At Kiel University, associated to Professor Rüdiger Schulz, the junior research group ‚Bioenergetics in Photoautotrophs' at the Botanical Institute, led by Dr Kirstin Gutekunst, investigates how this carbon cycle - and the resulting CO2 emissions - can be avoided during energy conservation. "For this purpose, the storage of solar energy directly in the form of hydrogen is particularly promising - this creates no CO2 and the efficiency is very high due to the direct conversion," says Gutekunst to explain her research approach. With her team, she investigates a specific cyanobacterium: via photosynthesis, it can produce solar hydrogen for a few minutes, which is however subsequently consumed completely by the cell. In their current study, the Kiel researchers describe how this mechanism could be used potentially for biotechnological applications in future: they were able to couple a specific enzyme of the living cyanobacteria, a so-called hydrogenase, with the photosynthesis in such a way that the bacterium produces solar hydrogen for long periods of time, and does not consume it. The scientists published their findings today in the renowned scientific journal Nature Energy.

Cyanobacteria as hydrogen factories

Just like all green plants, cyanobacteria are able to perform photosynthesis. During this process, solar energy is used to split water and to store the solar energy chemically - especially in form of sugar. Electrons pass through so-called photosystems in which they undergo a cascade of reactions that ultimately produce the universal energy carrier adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and so-called reducing equivalents (NADPH). ATP and NADPH are subsequently required for CO2 fixation to produce sugar. Thus, the electrons needed for the production of hydrogen are normally part of metabolic processes which provide the cyanobacteria with stored energy in the form of sugar. The Kiel research team has developed an approach to redirect these electrons and stimulate the metabolism of the living organisms to primarily produce hydrogen.

"The cyanobacterium we investigate uses an enzyme, a so-called hydrogenase, to produce the hydrogen from protons and electrons," says Gutekunst, who is also a member of the Kiel Plant Center (KPC) research network at Kiel University. "The electrons used in this process come from photosynthesis. We succeeded in fusing the hydrogenase with the so-called photosystem I in such a way that the electrons are primarily used for the production of hydrogen, while the normal metabolism continues to lesser extents," continues Gutekunst. In this way, the modified cyanobacterium produces significantly more solar hydrogen than in previous experiments.

Ability to repair itself

Similar approaches for hydrogen production by using fusions of hydrogenase and photosystem already existed in vitro, i.e. outside of living cells in test tubes, or on electrode surfaces in photovoltaic cells. However, the problem with these artificial approaches is that they are typically short-lived. The fusion of hydrogenase and photosystem must be laboriously re-created, again and again. In contrast, the path followed by the Kiel research team has the major advantage of potentially functioning indefinitely. "The metabolism of living cyanobacteria repairs and multiplies the fusion of hydrogenase and photosystem and passes it on to new cells during cell division, so that in principle, the process can continue permanently," emphasises project leader Gutekunst. "With our in vivo approach, we succeeded in producing solar hydrogen with a fusion of hydrogenase and photosystem in a living cell for the first time," she continues.

One of the current challenges is the fact that the hydrogenase is deactivated in the presence of oxygen. The 'normal' photosynthesis that continues in the living cells, during which oxygen is released by the splitting of water, thus inhibits the production of hydrogen. In order to remove the oxygen, or more specifically, to minimize the quantity released, the cyanobacteria for hydrogen production are currently partly switched to so-called anoxygenic photosynthesis. This is not based on water splitting. Therefore, the electrons for hydrogen production currently partly derive from water splitting and partly from other sources. But the long-term goal of the Kiel research teams is to only use electrons from water splitting for hydrogen production.

Concepts for the energy of the future

Overall, the new in vivo approach offers a promising new perspective for establishing photosynthetic water splitting as a means of production for climate-neutral, green hydrogen, and thus advancing the generation of sustainable energy. In the medium term, further research on the metabolic pathways of cyanobacteria in Gutekunst's group is particularly focussed on further increasing the efficiency of solar hydrogen production. "The research results of our colleague are an excellent example of how fundamental research on plants and microorganisms can contribute to solving social challenges," emphasises KPC spokesperson Professor Eva Stukenbrock. "We are thus making an important contribution in Kiel towards developing a sustainable hydrogen economy as a viable alternative for a secure energy supply of the future," continues Stukenbrock.

Links

Bioenergetics in Photoautotrophic Organisms, Botanical Institute, Kiel University: www.biotechnologie.uni-kiel.de/de/forschung/nachwuchsgruppe-bioenergetik-in-photoautotrophen/nachwuchsgruppe-bioenergetik-in-photoautotrophen

Forschungszentrum Kiel Plant Center (KPC), CAU Kiel:

www.plant-center.uni-kiel.de

Nature Energy 'News & Views' - Hydrogen comes alive:

https://rdcu.be/b3WBZ

Original publication

Jens Appel, Vanessa Hueren, Marko Boehm, Kirstin Gutekunst (2020): Cyanobacterial in vivo solar hydrogen production using a photosystem I- hydrogenase (psaD-hoxYH) fusion complex. Nature Energy Published: 4 May 2020

DOI: 10.1038/s41560-020-0609-610.1038

https://rdcu.be/b3WB1

Contact

Dr Kirstin Gutekunst

Junior research group - Bioenergetics in Photoautotrophic Organisms

Botanical Institute, Kiel University

+49 (0) 431 880-4237

kgutekunst@bot.uni-kiel.de

…